Neville Hill and I originally wrote this piece in early summer 2019, but never quite finished it. As all the excitement over fiscal rules ahead of the 2019 UK General Election kicked-off, we wrote up a précis which was published by FT Alphaville.

We then submitted a longer version to the Society of Business Economists’ annual Rybzynski Prize and were delighted to be shortlisted. Since then we have received a number of requests for the longer version. Here it is:

——————

Fiscal rules have never been so prevalent among nations, but most fiscal rules fall victim to charges of ineffectiveness, over-complexity, asymmetry and harmful pro-cyclicality. The succession of fiscal rules – national and supranational – to which the United Kingdom has made itself subject since 1992 are no exception. We argue for a new fiscal rule that might help secure fiscal credibility that is intuitive, counter-cyclical and potentially symmetrical.

Today the United Kingdom targets a falling debt stock as a percentage of GDP and a cyclically-adjusted budgetary balance over the medium-term. Eurozone member states are subject to a plethora of deficit constraints and an obligation to reduce the debt stock to 60% of GDP.

Most of these rules are being met. But these rules are no longer fit for purpose in a world where policy rates are low and central banks have little room to ease.

Why a fiscal rule?

The economic, political and social consequences of each of debt default and high inflation are severe.[1] And there appears to be a limit to the proportion of total economic output that can be directed by a government towards public debt service, bounded by political, social and financial market parameters.[2] Furthermore, while monetary sovereigns can always summon into existence more money to service debt, there are good reasons why they might not always want to.[3] As such there is a powerful imperative towards limiting or reducing debt on the part of governments seeking to maximise long-term fiscal flexibility.

But while long term fiscal sustainability is a goal upon which every government can agree, the short-term incentives to increase spending can prove politically irresistible.[4]

Fiscal rules are means by which governments can seek to bind themselves (and demonstrate to others that they are bound) to the masts of fiscal rectitude. And while mixed, the evidence suggests that episodes of significant debt reduction have been associated with the introduction and use of fiscal rules across a number of countries over many decades.[5]

Fiscal rules fall into one of four categories – budget balance rules (maximum deficit), debt rules (creating upper limits on government debt), expenditure rules (limiting growth of expenditure) and revenue rules (generally targeting revenue as a percentage of GDP). [6] Each of these approaches have sought to secure debt and, consequently, monetary sustainability. Debt rules go directly to target an upper bound for government debt stock, while the others provide intermediate targets that will restrain or reduce the level of government debt. The rules are all asymmetric – they instruct governments to cut deficits or debts, but do not set a lower bound, or instruct more expansionary policy. That may reflect the fact that they were largely designed in the wake of the fiscal and monetary policy failures of the 1960s-1980s, when there was a compelling need to demonstrate fiscal and monetary credibility.[7]

What’s the problem?

Existing fiscal frameworks recognise the prospective dangers attached to a high and spiralling stock of debt, but are not designed to see the dangers of inappropriate deleveraging. Pro-cyclical fiscal tightening (raising taxes and cutting government spending in the midst of a slowdown or recession) can be especially damaging to the economy,[8] and the rules described above, targeting maximum debt stocks or government deficits, are prone to signal the necessity of fiscal tightening at precisely the moment of maximum pain.[9] Critically, they assume that monetary policy will be free to administer short-term demand management and so may be mis-specified when rates are at or near the lower bound.[10]

And they willfully ignore information embedded in financial market prices, seeing markets only as prospective constraints to fiscal flexibility: a capricious and constant source of risk. This, as we discuss below, presents another source of asymmetry: governments cannot ignore the message of very high borrowing rates, no matter what their fiscal rules are.

Simply put, while any fiscal rule will be clunky, the existing rule set poses meaningful problems and dangers when policy rates are at or close to the lower bound, as they have been for the past decade.

A better fiscal rule

A key aim of fiscal rules is “sustainability”: to ensure public finances are managed to avoid the risk of default or inflation. And although the size of a government’s debt obviously has implications for sustainability, it is not the only metric that matters. Nor is it the most important.

Sustainability is the economic and political capacity of the state to meet its financial obligations. We think debt interest service as a percentage of GDP is a better metric than debt stock when it comes to capturing the concept of sustainability. When debt service is very high, governments find it challenging to dedicate tax revenues to paying coupons on bonds. But conversely, when it is low it would suggest there is room for fiscal expansion.

Debt service is a product not of stock alone, but of the size, tenure and type of existing debt stock, the growth in economic output, primary fiscal balance, choice of new issuance, and the level of market interest rates. These factors, furthermore, are interdependent.[11] In summary, debt service is a function of the past fiscal legacy that must be managed, the present economic environment that is ever-changing, and external expectations as to future economic and monetary conditions. Furthermore, it responds to changes in its determinants fairly slowly, especially if the debt and issuance tenure is long (see Appendix). That means fiscal rules based on debt service targets will generally only necessitate gradual changes in fiscal policy, not abrupt dislocative shifts.

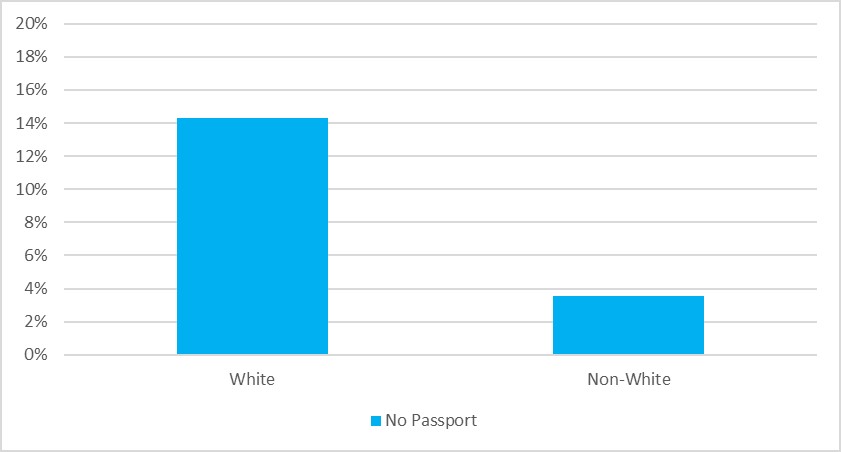

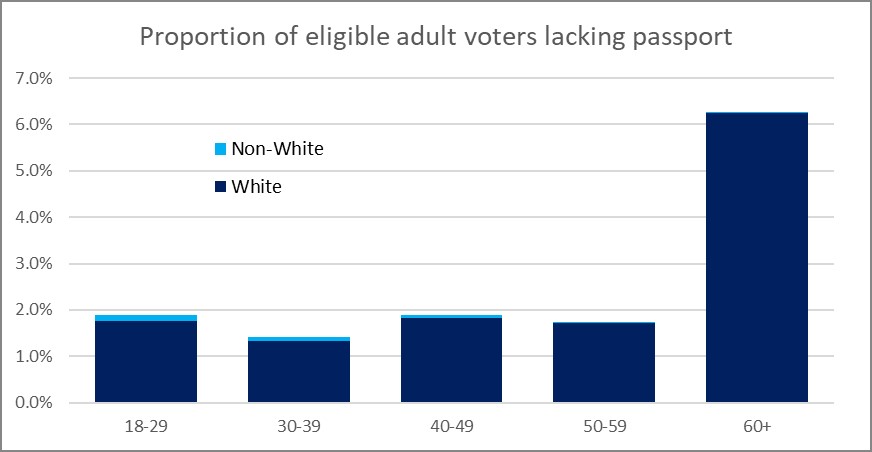

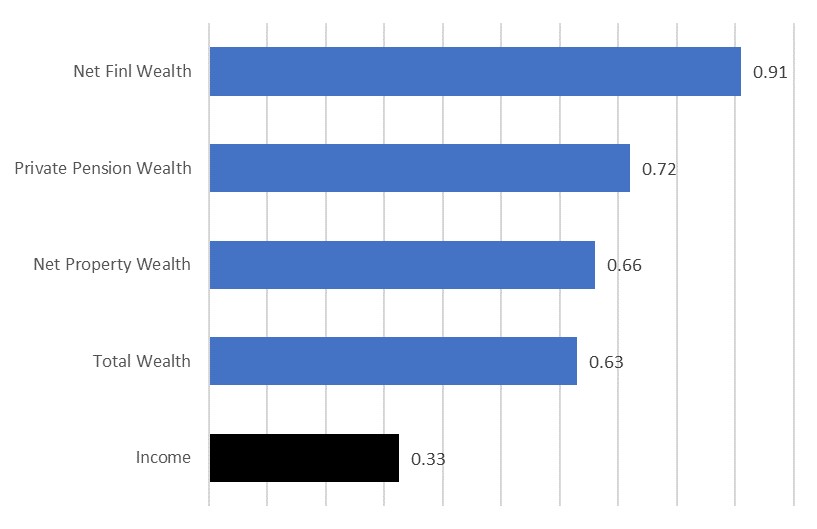

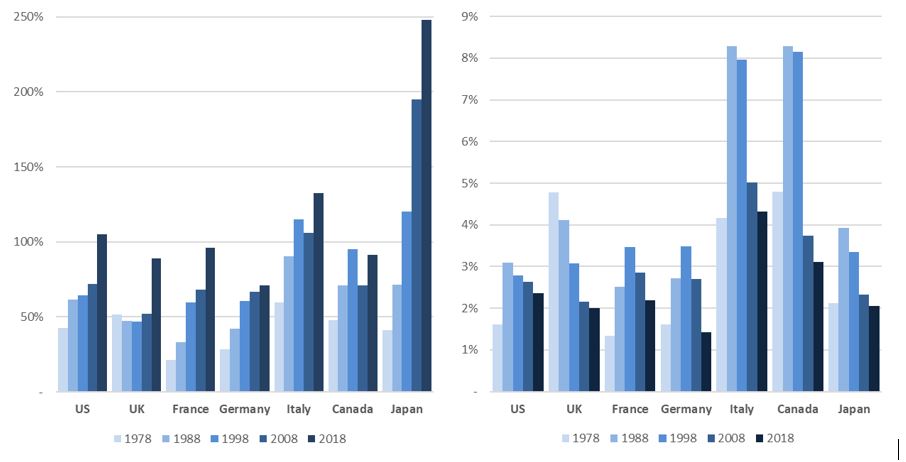

Debt stock and debt service then are related, but distinct. They can move in opposite directions for decades as a glance at recent United Kingdom budgetary history can show. In 1980 the United Kingdom spent 5.2% of GDP towards servicing government debt; debt to GDP stood at 46.2%. Fast forward almost forty years and we can see debt service as a percentage of GDP having fallen to 2.7% of GDP (2.0% of GDP after the fiscal impact of QE is taken into account), while debt to GDP had almost doubled at 89% of GDP. This startling fall in debt stocks and interest costs moreover is not unique to the United Kingdom (see Figures 1 and 2).

Figures 1 & 2: Debt stocks as % of GDP since 1978; Interest costs as % of GDP since 1978

Instances where interest costs have reached 5% of GDP have tended to be met by alarm in Finance Ministries, and fiscal adjustment programmes have tended to follow (Canada’s 1985 and 1995 Plans, Italy 1988 and 1995 Plans, the UK’s 1976 IMF programme and 1980 Medium-Term Financial Strategy).[12]

There have been multiple other instances where fiscal adjustments have been delivered by G7 governments – most recently the UK’s 2012-2020 programme of austerity that seeks to target debt stock. But as Blanchard and Tashiro (2019) argue in relation to Japan – where debt-to-GDP is more than 2.5X higher that seen in the UK and debt service is 30% lower than the UK as a percentage of respective GDP – the appropriate fiscal policy for the Ministry of Finance may well be an increase rather than a reduction in primary deficits over coming years, given the macroeconomic challenges of re-anchoring inflation expectations in firmly positive territory and delivering higher levels of economic growth while the Bank of Japan remains at the effective lower bound. A higher debt stock is not a desirable end in itself, but nor is it necessarily a greater danger than an inappropriately tight fiscal policy when debt service is low.

The reason for this fall in debt costs despite the surge in debt was the collapse of market interest rates. In 1980 long term Gilt yields stood at 13.9%, and by 2017 they had fallen to 1.0% This decline in market interest rates reflects changing market expectations of economic growth and inflation. But the fall in market interest rates from a fiscal policy perspective appears to have been taken as an event rather than as a signal. A government’s decision to ignore the information embedded in asset market prices short-circuits the ability of easy monetary conditions to prompt economically stimulative fiscal policy; refocusing fiscal rules towards debt service would remove this short-circuit. Fiscal rules focused on debt service also remove an asymmetry. As we have seen time and again in the past, markets pricing extremely high rates provoke or necessitate a restrictive policy from governments. But extraordinarily low borrowing costs do not provoke the opposite – a stimulative policy – as governments are often constrained by nominal targets for the stock of their debt or the size of their deficits.

A symmetrical fiscal rule?

While a new fiscal rule that targeted a maximum debt service ratio would be a vast improvement on the current fiscal rules, it is worth exploring whether there are further benefits to be had by also setting a minimum debt service ratio. We believe that so doing would deliver three principle benefits.

Firstly, it would introduce more powerful counter-cyclical fiscal impulse. The government would be prompted to take the initiative to invest when the cost of so doing was lowest, the need was at its highest, and the potential knock-on inflationary consequences of which would be helpful rather than counterproductive.

Second, it would introduce a mechanism by which fiscal and monetary policy coordination might be enhanced. Lower interest rates – signalling expectations that economic output was far below potential – would prompt a looser fiscal policy to boost output, while higher rates would prompt fiscal retrenchment.[13] Furthermore, when the central bank undertakes large scale purchases of government debt (QE) it not only reduces interest rates in government bond markets, but government debt interest is reduced further by the central bank returning the difference between its policy rate and the yield to maturity of the government bonds it holds back to the government. At present, that reduces UK government debt service by 0.7% of GDP.

Thirdly, introducing a policy that forcefully and automatically addresses the Keynesian ‘liquidity trap’ removes downside uncertainty over the course of long-term economic growth and inflation. As such its adoption could keep interest rates and long-term bond yields at higher levels than they would otherwise be, and other UK financial assets might attract a reduced risk premium (associated with the prospect of obviating stagnation). But the symmetrical nature of the rule would also provide assurance that fiscal contraction would come onto the agenda if inflationary expectations became unanchored.

Again, we believe more research is required before a target for the lower bound of debt service is selected but would envisage that it would reasonably be around 2% of GDP. In 2018 the United Kingdom’s debt service costs amounted to 2.7% of GDP before the fiscal dividends of QE are counted and 2.0% after.

Most fiscal rules fall victim to either the charge of ineffectiveness, over-complexity or harmful pro-cyclicality. The succession of fiscal rules – national and supranational – to which the United Kingdom has made itself subject since 1992 are no exception. We believe that this proposal is worthy of examination as a potential exception to this charge sheet.

==============

Appendix: Term of debt matters

When looking at a government’s debt dynamics we can see that term structure matters. Among developed bond markets included in the Bloomberg Barclays Global Treasury index, the UK has the longest average maturity (figure 2.1) – standing at more than twice the weighted average maturity of US government debt. Looking more closely at the UK’s refinancing requirements, we can see that they fall unevenly across time as principal and interest payments are, by their nature, somewhat lumpy (figure 2.2).

Figures 2.1 and 2.2: Weighted average maturity of developed government bond markets; Term structure of UK government debt, June 2019 – assuming RPI yoy at 3%

Bond market yields – determined by the price at which investors are willing to buy existing bonds in the secondary market, and rates of interest at which borrowers are willing to originate new borrowings – can vary meaningfully from decade to decade. The term of existing and new borrowings impacts how quickly these market-driven yields will inform fiscal sensitivities.

The relatively high term length of UK debt reduces the fiscal sensitivity to changing market expectations around the future course of the Bank of England’s Bank Rate, economic growth, and inflation (where a drop in each of these has historically corresponded to a fall in market yields).

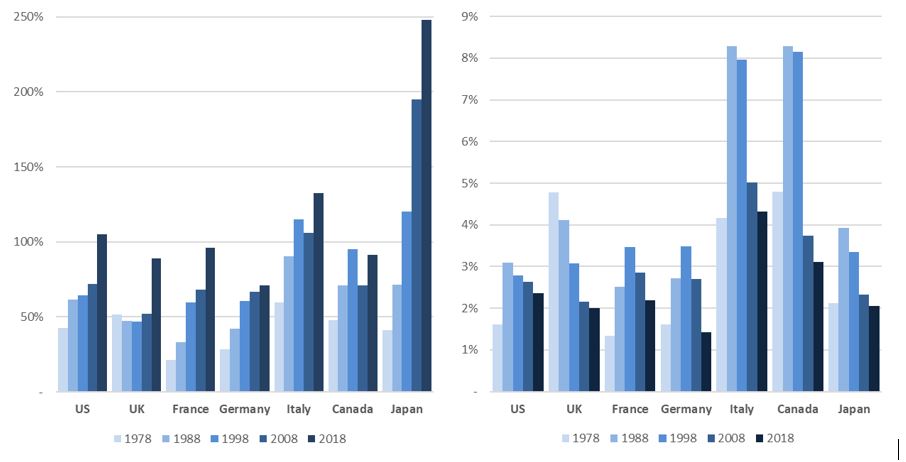

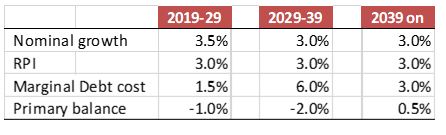

To illustrate this let’s consider a (relatively bleak) scenario for the UK (table 2.1) over the next fifty years. In the first decade we model bond yields at levels not too distant to where they are today, sluggish nominal GDP growth, and a primary deficit (government budget balance before interest costs) of 1.5% of GDP. This scenario is consistent with a stable debt stock as a percentage of GDP, and gradually falling debt service costs.

From 2029-2039 we model a shock to bond yields, rising dramatically to 6%, nominal growth slowing to an even more derisory 3% per annum, and a larger primary deficit of 2% of GDP per annum. From 2039 onwards, we model a combination of continued derisory nominal GDP growth, a fiscal tightening such that the government runs a small primary surplus, and a fall in bond yields to 3%. The Retail Price Index (to which current inflation linked Gilts are indexed) is modeled to stay steady at a growth rate of 3% per annum.

Table 2.1: scenario to illustrate the implications of financing term

Figures 2.3 and 2.4 show how the modeled scenario can have quite differing implications for both the fiscal cost of debt service and for the contemporary stock of debt as a percentage of GDP. The purple line assumes that primary deficits and refinancing needs are met exclusively through the issuance of new five-year bonds at the modeled marginal bond yield (which is assumed to be stable across all maturities). This choice of tenor sees interest costs rise rapidly to 7% of GDP between 2029 and 2039 before receding even more rapidly to 4% over the subsequent five years. Debt to GDP rises from 2029 until 2044 when it reaches 135% before beginning a glacial decent, reaching 127% by 2071. The grey line illustrates the impact using the same assumptions but this time assuming that financing needs are met through the exclusive issuance of ten-year bonds. The light blue line shows the impact of issuing exclusively twenty-year bonds and the dark blue the impact of issuing exclusively thirty-year bonds.

Figures 2.3 and 2.4: Interest as a % of GDP; debt as % of GDP

Concerns that a fiscal rule associated with the fiscal costs of debt service rather than debt stock might put the government at the mercy of markets capture a truth that governments’ fiscal costs of debt are determined in part by market yields.

But every government seeking to finance its expenditures through the bond market will already be sensitive to market yields; the degree to which governments have heightened or dampened sensitivity to market movements is very much in their control of their debt management functions. Shifting to a fiscal rule that focused on debt service would put the question as to how much sensitivity the government wanted to have to market rates firmly in the hands of the hands of the government.

References:

Blanchard, O. 2019. ‘Public Debt and Low Interest Rates’. American Economic Review 109, no. 4: 1197–1229 https://www.aeaweb.org/aea/2019conference/program/pdf/14020_paper_etZgfbDr.pdf

Blanchard, O & Leigh, D. 2013. ‘Growth Forecast Errors and Fiscal Multipliers’, IMF Working Paper No 13/1 https://www.imf.org/~/media/Websites/IMF/imported-full-text-pdf/external/pubs/ft/wp/2013/_wp1301.ashx

Blanchard, O. & Tashiro, T. 2019. ‘Fiscal Policy Options for Japan’, PIIE Policy Brief 19-7, May 2019. https://piie.com/system/files/documents/pb19-7.pdf

Borensztein, E. & Panizza, U. 2008. ‘The Costs of Sovereign Default’, IMF Working Paper 08/238, 2008. https://www.imf.org/~/media/Websites/IMF/imported-full-text-pdf/external/pubs/ft/wp/2008/_wp08238.ashx

Broadbent, B. 2014. ‘Monetary policy, asset prices and distribution’, speech given a the Society of Business Economists Annual Conference, October 23. https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/-/media/boe/files/speech/2014/monetary-policy-asset-prices-and-distribution

Debrun, X. & Kumar, M. S. 2007. ‘Fiscal Rules, Fiscal Councils and All That: Commitment Devices, Signalling Tools or Smokescreens?’ in: Banca d’Italia (eds.) Fiscal Policy: Current Issues and Challenges, Papers presented at the Banca d’Italia workshop held in Perugia, 29–31 March 2007, pp. 479–512. https://www.bancaditalia.it/pubblicazioni/altri-atti-convegni/2007-fiscal-policy/Debrun_Kumar.pdf?language_id=1

Fischer, S. 1996. ‘Why are Central Banks Pursuing Long-Run Price Stability?’ Jackson Hole Symposium, August. https://www.kansascityfed.org/publicat/sympos/1996/pdf/s96fisch.pdf

HM Treasury, 2017. Charter for Budget Responsibility: autumn 2016 update. January. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/583547/charter_for_budget_responsibility_autumn_2016_update_final_for_laying_web.pdf

Hughes, R., Leslie, J. & Pacitti, C., 2019. ‘Britannia waives the rules?’, Resolution Foundation, October. https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/app/uploads/2019/10/Britannia-waives-the-rules.pdf

IMF, 2002. Assessing Sustainability, May. https://www.imf.org/external/np/pdr/sus/2002/eng/052802.pdf

IMF, 2009. ‘Fiscal Rules – Anchoring Expectations for Sustainable Public Finances’, Fiscal Affairs Department, December http://www.imf.org/~/media/Websites/IMF/Imported/external/np/pp/eng/2009/_121609pdf.ashx

IMF Fiscal Rules Dataset, 1985-2015. http://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/fiscalrules/map/map.htm

Lledó, V., Sungwook, Y., Fang, X., Mbaye, S, Kim, Y. 2017. ‘Fiscal rules at a glance’, International Monetary Fund, Washington DC, March. https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/fiscalrules/Fiscal%20Rules%20at%20a%20Glance%20-%20Background%20Paper.pdf

Mauro, P. (ed). 2011. Chipping Away at Public Debt: Sources of failure and Keys to Success in Fiscal Adjustment, John Wiley & Sons.

Mauro, P., Romeu, R., Binder, A., & Zaman, A. 2013. ‘A Modern History of Fiscal Prudence and Profligacy’, IMF Working Paper No. 13/5, International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2013/wp1305.pdf

Portes, J. & Wren-Lewis, S., 2014. ‘Issues in the Design of Fiscal Policy Rules’, Department of Economics Discussion Paper Series No.704. May. https://www.economics.ox.ac.uk/materials/papers/13342/paper704.pdf

Rogoff, K. 1987. ‘Equilibrium Political Budget Cycles’, NBER Working Paper 2428. http://www.nber.org/papers/w2428.pdf

Romer, C. D., & Romer, D.H. 2019. ‘Fiscal space and the aftermath of financial crises: how it matters and why’, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, BPEA Conference Draft’, March 7-8. https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Fiscal-Space-and-the-Aftermath-of-Financial-Crises.pdf

Summers, L.H. 2014. ‘US economic prospects: secular stagnation, hysteresis and the zero lower bound’, Business Economics Vol 49, No2. National Association for Business Economics. http://larrysummers.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/NABE-speech-Lawrence-H.-Summers1.pdf

[1] See for example Borensztein. & Panizza. (2008), Fischer (1996).

[2] See IMF (2002) on the degree to which fiscal sustainability can be understood as a political concept.

[3] While the limiting factor on private sector or foreign-currency-denominated sovereign indebtedness is creditworthiness, the degradation of which can be observed in financial instability, the limiting factor on monetary sovereign debt and deficits is the acceptability of the currency, the degradation of which is manifest in monetary instability – via currency weakness, inflation, and/ or a fracturing of the financial system.

[4] These are the so-called ‘shortsightedness’ and ‘common pool’ problems. For shortsightedness see Rogoff (1990); for ‘common pool problem’ see Debrun and Kumar (2007).

[5] Debrun and Kumar (2007), IMF (2009).

[6] See IMF Fiscal Rules Dataset (2016) for a catalogue of past and present fiscal rules at the national and supranational level, and Lledó, et al (2017) for a history of fiscal rules by country.

[7] Sovereign debt markets exist not only to finance government deficits (or rather sterilise the monetary impact of fiscal payments in excess of tax receipts), but also to provide funding benchmarks for private bond issuers, and to serve as high quality collateral for the domestic financial system. Sovereigns not requiring external financing have issued full yield curves of benchmark securities for these reasons.

[8] Blanchard & Leigh (2013).

[9] Romer & Romer (2019) examine the motivations attached to large and small-scale episodes of austerity across the OECD since 1990 and find instances where the communicated rationale for pro-cyclical austerity was misplaced fear of loss of market access.

[10] This criticism is certainly not universal, with Wren-Lewis and Portes (2017) and Hughes, Leslie & Pacitti (2019) notable attempts to incorporate monetary constraints to a fiscal rule. Towards the end of 2019 the Conservative Party announced that the UK’s fiscal framework (requiring a cyclically-adjusted deficit below 2% by 2020-21 and the delivery of a reduction in the net debt to GDP ratio each year unless the Treasury judges that there has been a ‘significant negative economic shock to the UK economy’ (HM Treasury 2017)) would be replaced by a requirement to run a balanced current budget excluding capital expenditure from 2022, a 3% of GDP limit to net investment and a 6% of tax revenues maximum for debt interest costs, beyond which government must reassess its borrowing plans with the goal of stabilizing debt stock. While a step in the right direction, this approach retains the asymmetry of previous fiscal rules.

[11] A simple shorthand for estimating the change in debt as a percentage of GDP is the equation: , where r and g represent the interest rate and growth rate respectively (in either real or nominal terms), while d and p represent the stock of debt and primary surplus (each as a proportion of GDP). Setting Δd to zero delivers a framework for achieving a stable debt to GDP ratio. Simply put, a higher rate of economic growth, a lower interest rate, and a higher primary budget surplus are all things that help to reduce debt stock.

[12] See Mauro (2012).

[13] There is a further question as to whether a symmetric fiscal rule should be set to target interest costs net of the Bank of England’s Asset Purchase Facility (APF) payments. Doing so would turbo-charge monetary-fiscal coordination by delivering to the Bank of England a mechanism to provide direct and immediate fiscal space that must be deployed by the Treasury if the lower bound of interest costs as a percentage of GDP was not to be breached. This is because coupons paid on the gilts held in the APF by the Treasury are returns to the Treasury (minus financing costs) , and as such quantitative easing: a) delivers real fiscal dividends in the form of a lower net interest cost; b) could require the Treasury to ramp up debt issuance such that the minimum debt interest payment rule was met. The degree to which such levels of coordination would threaten the Bank’s independence and institutional credibility need though to be considered in weighing this option, as would the costs of unwind.